Barnstable citizens at the station that day in July 1945 must have watched popeyed as newly arrived passengers from the New York train mounted a western stage coach in time for the grinning driver to rouse his four horses with a crack of the whip.

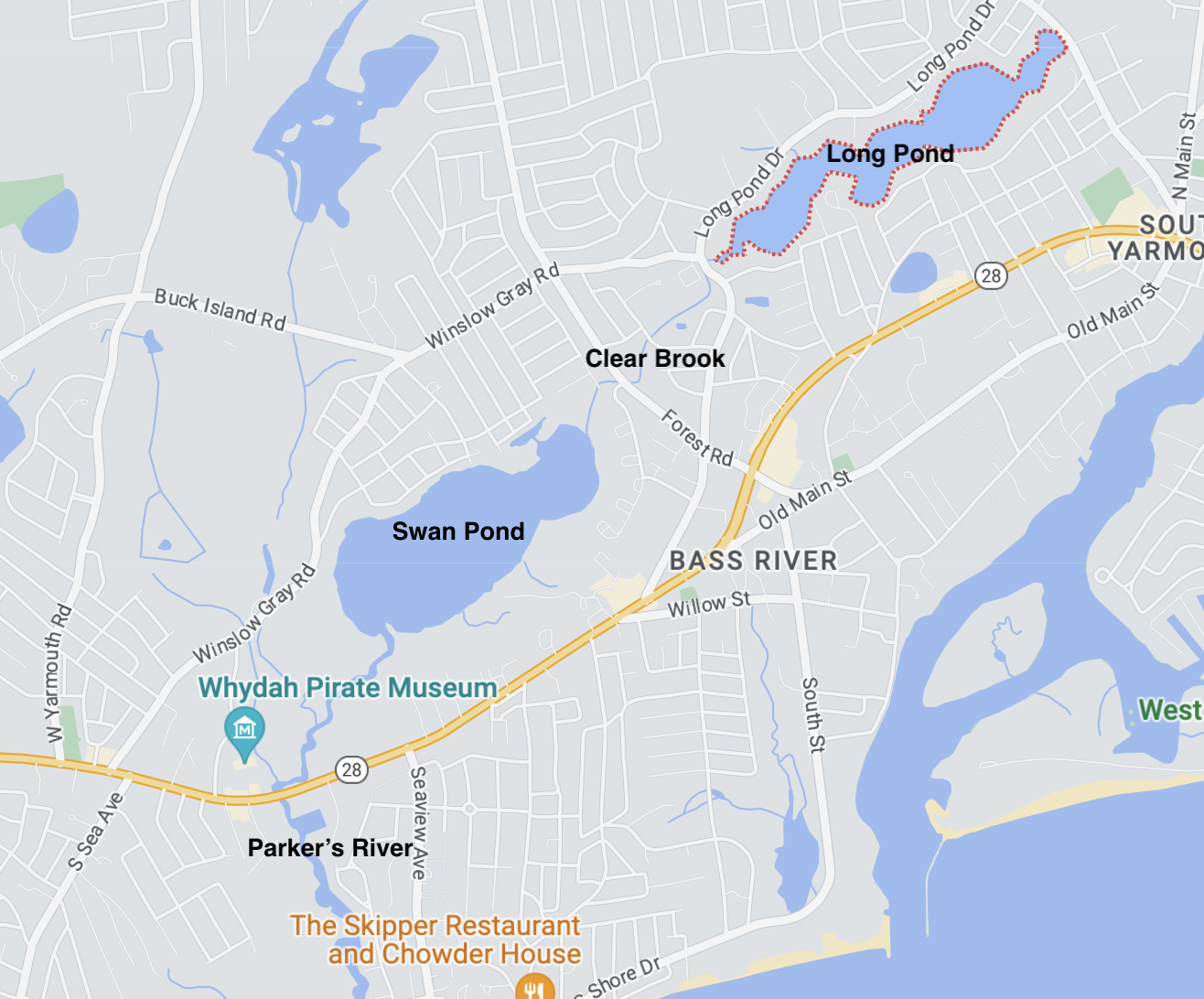

Even more surprised, if not amused a few days earlier, were motorists on the Old Kings Highway to find their progress slowed by cowboys driving a herd of horses as far as Bonehill Road in Cummaquid.

And why did that gentleman in five gallon hat and western boots strolling along Barnstable Village Main Street remind us of Roy Rogers? Because … he was Roy Rogers.

Roy Rogers.

Before our astonished witness could swear “never to touch another drop” he would discover that these western anomalies were all associated with Cape Cod’s recently opened “dude ranch.”

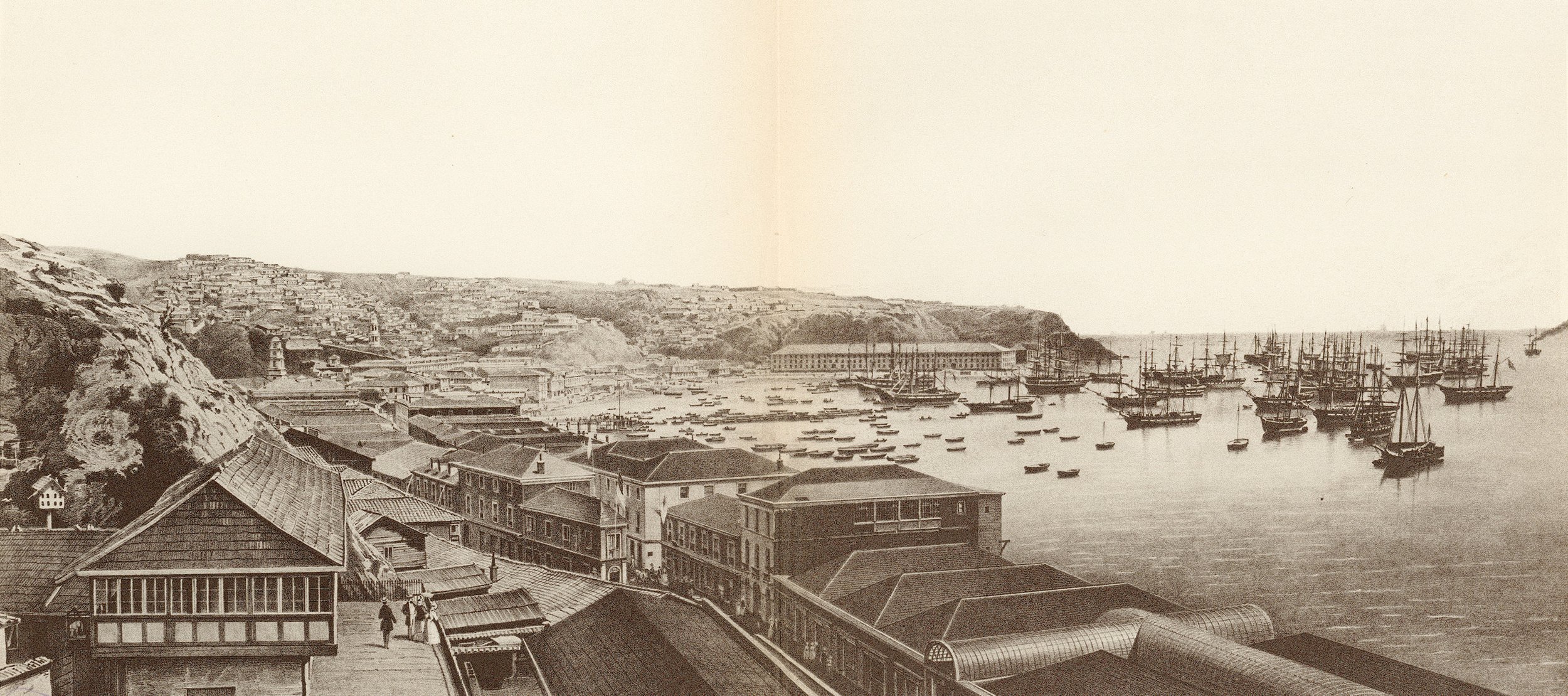

Their destination was a rustic imposing building sprawling along the heights overlooking Barnstable Harbor and Sandy Neck. Today the rambling structure that later housed the Harbor Point Restaurant stands empty, with an ancient millstone for its doorstep. Also near the front door was a large grindstone which once belonged to the Swift family who ran the local abattoir for butchering livestock. Bonehill was then known as “Slaughterhouse Road” before members of the family moved to Chicago to create one of the country’s leading meat packing companies.

Noted for its fine dining, elegant wedding receptions and sweeping views of Barnstable Harbor and Sandy Neck, the Harbor Point restaurant had many other names and colorful diversions in its 100 year history.

The property was originally developed in 1902 as a summer home for the Johnson family of New York. Mr. Johnson was a silk merchant of considerable influence, as evidenced by the fact that railroad officials would hold the train when Mr. Johnson was delayed on Friday nights leaving his office for the weekend on Cape Cod.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, the gracious family home under new ownership had metamorphosed into a favorite joint of local sports and flappers because of its secluded location convenient to the quiet delivery of “supplies” via Barnstable Harbor.

Bob Borino, the former restaurant manager, would show interested visitors a secret closet in one of the bedrooms with its trap door, where rum runners brought up the liquor.

By the 1930s, the establishment had become notorious as a house of ill fame, although the archives are lacking in details on this phase.

In the early 1940s, Floyd van Duzer was ready to retire from his machine shop in Quincy, and pursue his yen to raise livestock on Cape Cod. According to Caleb Warren, writing in the Cape Cod Business Journal (June 1982), Van Duzer was shown “a hundred acres with a mile of beach and a well built house” in Cummaquid for $60,000. He offered $15,000 and the spread was his, with even more buildings than he had known about. Being a real adventurous type, and encouraged by his wife, who had western connections, and stalwart sons, he conceived the idea of a dude ranch.

After the town of Barnstable issued a permit in 1944, van Duzer began searching the rodeo circuit out west to find a suitable manager. He came up with Blackie Karman from Encampment, Wyoming, “once voted the best all round cowboy after a rodeo in Madison Square Garden.” He turned out to be a creative, if unpredictable, foreman. He convinced Van to buy some 30 horses “never ridden before,” which created a problem when cowboys and horses came off the train at Barnstable station. The horses made straight for the green grass of the court house lawn, and during the drive down Old Kings Highway to Bonehill Road they created confusion at the Sunday services of St. Mary’s Church.

But, by the summer of 1945, Blackie had the ranch rolling with weekend rodeos, “featuring champion cowboys, bull riding, calf roping, bronc riding and trick roping etc.” In the first rodeo, June 23, 1945, the Barnstable Patriot reported that Cummaquid farmer Frank Taylor, “stole the show” from Blackie Karman and his cowhands from Texas and California. He won the “pipe race” and “and rode with the best of them when he handled the brake on the stage coach as the four horses whirled the top heavy vehicle in figure eights.”

As publicity spread and brochures were distributed, guests came from all over New England, and especially New York. The stage coach would “roll ‘em in and out” on weekends at Barnstable station.

In addition to the amenities of beach and surf, the Ranch offered some real western delights. The ranch cowboys led horseback excursions at low tide across the flats of Yarmouth to East Dennis, and “overnighters” to Provincetown. They even found a way to ride galloping horses towing water skiers. There were parades down Main Street in Hyannis to arouse interest in the weekend rodeos (admission $1 for adults, 50 cents for children.) Roy Rogers and other cowboy film stars occasionally visited.

The ranch produced its own vegetables, milk, butter and cream, and served up seafood from the local fishermen. According to Van Duzer, a goodly portion of the clientele came from New York, including many young women from advertising agencies.

The price seemed to be reasonable at $60 per week in a bunkroom, and $85 for a private room.

Blackie perhaps got carried away with offering the guests western style entertainment when on Labor Day he pulled his six gun and shot out all the windows in the Ranch House. He was fired thereafter.

The Dude Ranch kept on ridin’ and ropin’ until 1948, when Van Duzer sold out. The new owners continued the food service as the Cape Cod Ranch Smorgasbord -- “all you could eat for $3.25” -- until 1979. In the 1980s, new owners renovated the establishment to create the Harbor Point Restaurant for “casual fine dining.”

Presumably the cowboys long ago had ridden off with their horses into the sunset.

by Haynes Mahoney